Uighurs in NL, the forgotten refugees

Fleeing from chinese “re-education camps” always more muslim Uighur refugees arrive to the NL, and they strive not to be forgotten

By Vittoria Malgioglio and Federico Campanile

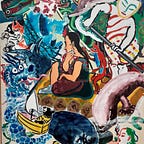

In Amsterdam, the mild autumn is giving way to the winter’s rain and wind, but despite the cold, the streets of the Neuwe Pijp district remain crowded. Along the narrow city centre streets, in the midst of a mix of Dutch postcard houses and hipster bars, there is also a small Uighur restaurant. Inside, the traditional music instruments fixed to the wall, the smell of spices in the hall, and a feeling of genuine conviviality tell the story of a nation, East Turkestan, which for the international community does not exist and for the People’s Republic of China is the autonomous region of Xinjiang.

For Chinese authorities, the peculiar cultural identity of the Uighurs represents a factor of instability: different from the Han Chinese, the Turkish-speaking and Muslim Uighurs are organized on a tribal model and originated in the north-west of the country. Because of the policies of social control pursued by the central government, the Jordaan-based restaurant could soon be among the last remaining testimonies of the Uighur culture.

Preserving identity

Enver, editor for the Uighur Times, is thousands of kilometres away from his homeland in the west of China. In the safety of the Amsterdam restaurant, he can freely talk to 31mag about his people, without having to look around. And he can also give voice (in English) to the testimony of Obul Qasim: “I work at the East Turkestan Education Centre in Zeist, founded in 2009,” says Obul, who also works as a taxi driver in Utrecht.

His organization has just purchased a new building and schools in four Dutch cities. Here students can spend weekends and holidays: “It is essential for our community to preserve the identity that the Chinese government is trying to erase in every way,” he says seriously. The problem of not dispersing traditions is very felt by minorities, but for the Uighurs it is a question of survival: “China is trying to erase our uniqueness, so in the Netherlands, where we are free, we try to pass on to our children the language and the traditions of our people”. Enver and Obul say that their wives and children are in the Netherlands, but that they haven’t had any news from the rest of their families in years.

In Europe, the claims of this stateless people are being heard, but the claims of the Uighurs have not broken through — like those of the Kurds, the Sarawis, or the Palestinians. Yet the “re-education camps” — as described in the 2018 report by the UN Commission for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination — would be real lagers where about one million Uighurs are imprisoned. The camps would be set up in an attempt to assimilate the Muslim minority into the multi-ethnic Chinese nation. This makes the UN rather uncomfortable, but for Beijing, the problem does not exist. The Uighur governor of the Shohrat Zakir region describes the camps as “voluntary vocational training centers”. So the Chinese insist, no attempt to erase Uighur identity, just an effort to combat extremism and separatism.

Obul has been away from home for a long time and has lived in Yemen and Turkey: a popular destination among the members of his community because of linguistic similarities and the shared faith of Islam. Then, from Turkey, he moved to the Netherlands. There are about 30,000 Uighur refugees in Turkey, and Turks have often mobilized for the cause despite Chinese pressure to lower Ankara’s profile of support.

“The Uighur language is similar to Turkish, so it’s easy to communicate with Turks,” says Obul. In China, Uighurs can only study Mandarin, so few learn English. “Once in the Netherlands, some of us manage to learn Dutch and integrate, but for many other people, the language is a big obstacle and they end up interacting only with the Turks”. Apparently it is a necessity, rather than real cultural proximity, that pools the two communities together.

But this is not just a matter of international politics: for Ankara the Uighur question is also an internal stability problem. “Unlike what happens with Syrian refugees, the cultural and linguistic similarity between the indigenous Turkish community and the Uighur minority requires the Turkish government to make greater efforts to support its nationalist claims,” explains Işık Kuşçu to 31mag.nl. She is Associate Professor at the METU in Ankara, specialised in Central Asian diasporas, she published an intriguing framework on the mobilization of the Uighur diaspora in 2017.

A distinctive line

Despite the small number of Uighur migrants in Turkey, this community may be an internal factor of instability for Ankara. At home, as well as in the Netherlands and Germany, Turks tend to mark a distinctive line between themselves and other Turkish-speaking populations: “Nationalism, as with Syrians living in Turkey, plays a central role. In Turkey,” says Işık Kuşçu, “the claims of the Uighurs are often being exploited not only for political reasons but also by the religious community as an example of anti-Islamic repression.” The Turkish authorities, in this sense, try to play on two tables: “On the one hand, Turkey does not want to create tensions with Beijing, on the other, it tries to divert the claims on a ground of religious brotherhood. For this reason, the emigration of the Uighurs towards Europe is a positive element for Turkey”, concludes Işık Kuşçu. This Machiavellian strategy seems to be aimed at avoiding dangerous ethnic juxtapositions that could undermine Erdogan’s nationalist propaganda.

According to the professor, it would precisely be the deep-rooted presence of Turkish communities in Germany and the Netherlands that pushes the Uighurs to emigrate to these countries. “Surely the two communities are in contact. It would be interesting to study better the forms of interaction between Uighurs and Turks”. The increasingly widespread debate on the re-education camps in Xinjiang has led to a wider interest in the Uighur diaspora, says Prof. Kuşçu. “A growing number of Uighurs are planning to move to Europe, so governments have begun to ask questions. Why are they leaving their country? Should we grant them political asylum?”

Obul welcomes the Dutch government’s attitude towards its people: the Netherlands would have supported their cause with conviction, especially after 2009. As Obul explains, “in 2009, during the Ürümqi riots, the Chinese government killed thousands of people. Only then did our cause gain notoriety in the eyes of the world.” Enver was in Ürümqi in those days and was trying to pick up his brother from the train station when rivers of Han Chinese invaded the streets of the city. The immediate consequence of the Ürümqi riots was an increase in asylum seekers from East Turkestan. The subsequent repression of Beijing resulted in the ramification of the Uighur diaspora into numerous associations around the world including the World Uighur Congress.

As Obul explains, “this is the first association that brings together and represents the entire community”. The congress is led by Dolkun Isa, who fled China at the end of the 1980s and is now a German citizen, of whom Obul respectfully recounts: “Isa spends less than forty days a year at home and works day and night to talk about the Uighurs to the whole world”. Rebiya Kadeer, former millionaire now living in the USA is known as the spiritual mother of the Uighurs and another very respected leader.

A political diaspora

The diaspora would be progressively turning into a less elitist and more popular movement than the community of origin. Also, the participation of those involved in political activities would be growing. “Many Uighurs still have relatives in China and are concerned about their safety. Although most of the time they are not active in politics, these people help their people by giving language courses and by dealing with immigration procedures,” says Işık Kuşçu. Thanks to the advent of digital information the issue was brought to the attention of a wider audience. Moreover, the receptivity of European civil society is growing, and governments are opening up institutional platforms for discussion to diaspora leaders. Hence, the Uighurs feel more taken into account today than in the 1990s, when the first movements were born in Turkey. Yet, given its geopolitical and commercial weight, China is not just any country, and while the European Union is particularly active in promoting human rights, governments are still very cautious in criticizing the Middle Kingdom.

“I don’t see a real interest in the issue [in part of governments] because of the risks of undermining the relationship with an extremely important country like China,” says Alessandra Cappelletti, professor at Xi’an Jiaotong Liverpool University. “The Uighur cause finds support more on a political level, rather than on an institutional one. In Europe, there certainly are parties that support the cause, but at the level of governments, I would be less convinced.” Further, the teacher does not see any clear and substantial pro-Uighur stance in the motion filed in July by 22 UN countries against the alleged violation of human rights in Xinjiang: “I do not think that the arguments contained in the text are substantive”, she says to 31mag. In addition, the religious factor also plays its part: the Uighurs are Muslims and many Western governments, Cappelletti says, could find it inconvenient to openly support an Islamic minority.

“Persecution”

The expert, moreover, disputes the very use of the term “persecution”: “Does it make sense to speak of persecution if the population is within Chinese territory? Xinjiang is a territory annexed by China in 1759 and therefore, under international law, part of the territory of the People’s Republic. I think it is wrong to speak of persecution because religious restrictions apply to the entire Chinese population.” For the Italian teacher, religious cults are all treated in an equal (and harsh) way in China, regardless of ethnic origin. “We create the case, but for Beijing the Uighurs are Chinese like the others.”

Another central question is that of the unity of the diaspora: is there a Uighur nationalism? “A true and proper nationalism has never formed in East Turkestan; the sense of Uighur belonging develops at a local level with a strong attachment to the oasis. Moreover, among the Uighurs, we can see a diversity of recognition of the leader. Rabiya Kader and Dolkun Isa are very quarrelsome among themselves, the community is not united, there is no leadership, especially because of the lack of political thinkers and leaders.”

Originally published at https://www.31mag.nl on October 31, 2019.